Distortions of space and time in and around objects and events

Look out at the world around you. What do you see? Perhaps the denizens of a coffee shop, a crowd of people waiting in line, or a car parked just outside. Listen to the world around you. What do you hear? A steady drone of background noise, an occasional laugh, the hums and whirs of traffic through the glass. You see and hear not arbitrary ‘stuff’ but structure in the world around you. That is: You see objects, and you experience events. In a ‘blooming, buzzing’ world, objects and events are the structure. Like atoms or molecules are the ‘units’ of matter, objects and events are the units of experience.

The demarcation of our experience into structured units is not without consequence: Like gravity bends space and time in the physical world, objects and events bend space and time in the mind — resulting in a wide range of remarkable illusions, some of which you can see for yourself below.

This page contains demonstrations from a paper (w/ MomentsLab.org) on distortions of space and time. The purpose of this page is to allow people to experience certain illusions with and without guiding lines.

Figure 1. Various illustrations of object-based warping and the one-is-more illusion. (A) The canonical object-based warping effect wherein dots within the rectangle are perceived as further apart. (B) Variations of object-based warping. (C) Object-based warping near rather than within objects. (D) The canonical one-is-more illusion wherein continuous entities are perceived as ~30% longer than discrete entities. (E) The one-is-more illusion persisting through occlusion. (F) An example of the bi-stable ‘apple core’ image used to show the one-is-more illusion is evident even when visual input is perfectly equated (dashed lines are to highlight possible interpretations; they are for illustrative purposes only). In all cases, the relevant extents are highlighted with dotted lines; note that these illusions appear stronger without these guiding lines.

Figure 2. Other illusions of spatial extent. (A) Variations of object-based warping, without clear objects. (B) Two examples of the Oppel-Kundt illusion wherein the extent across many lines/dots is perceived as greater than the extent across empty space. (C) The Coren-Girgus illusion wherein dots between sets are perceived as farther apart. (D) The open-object illusion. (E) The pint glass illusion. In all cases, the relevant extents are highlighted with dotted lines; note that these illusions appear stronger without these guiding lines.

Figure 3. Illusions of spatial location. (A) Two examples of spatial compression wherein locations are either compressed towards each other or toward a center point. (B) An example of prototype effects wherein objects are mislocalized towards the centers of their respective quadrants (using data from Yousif, Chen, & Scholl, 2020). (C) The classic oblique effect whereby oriented bars in the oblique region are harder to perceive. (D) A visual explanation of oblique warping, which describes various other oblique distortions.

Figure 4. Temporal analogues of illusions of spatial extent. (A) Event-based warping wherein probes within a continuous event appear further apart in time. (B) The (temporal) one-is-more illusion wherein continuous periods of time are perceived as longer than discontinuous ones. (C) Variations and extensions of the one-is-more illusion, or event-boundary contraction. (D) The ‘Memento’ effect, wherein events played in a reverse order are perceived as shorter in duration. (E) Two variations of the filled-duration illusion wherein the filled durations are perceived as longer. (F) Illustrations of how these illusions apply to silence as well as sound. In all cases, the relevant extents are highlighted with dotted lines.

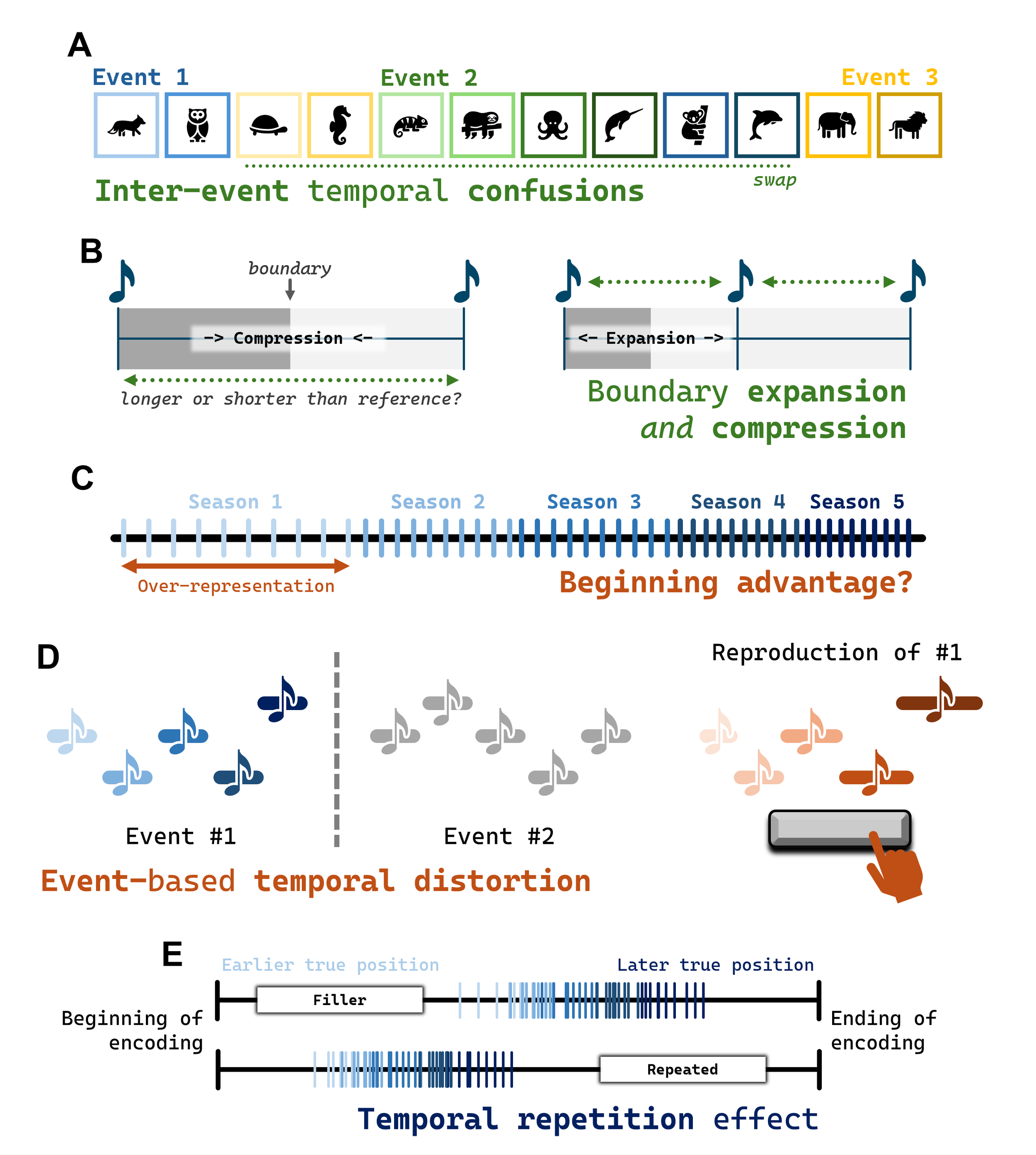

Figure 5. Other event-related temporal distortions. (A) An illustration of temporal confusions caused by event boundaries. (B) Two contradictory temporal distortions resulting from different time perception manipulations (per Bangert et al., 2019). (C) An illustration of a ‘beginning advantage’ whereby beginnings are overly represented on mental timelines (per Yousif et al., 2024). (D) An example of an ‘event-based temporal distortion, whereby beginnings are compressed and endings are expanded (per Wen and colleagues, 2025). (E) The temporal repetition effect wherein repeated items are perceived as initial occurring longer ago (per Sherman and Yousif, 2025). In all cases, the relevant extents are highlighted with dotted lines; note that these illusions appear stronger without these guiding lines.